Learning in the era of mass production: Lessons from the Renaissance

I knew I had to read Leonardo da Vinci’s biography when I came across this post:

I was eager to understand why he made those lists, what was on them, and how he managed to check off its items. But more than a deep (869-pages deep) understanding of Leonardo’s methods to feed his curiosity, this book gave me an inside look into the context where he actually learnt to learn.

At the age of fourteen, Leonardo started an apprenticeship at Andrea del Verrocchio’s workshop in Florence. You might be picturing a spacious and radiant studio, where artists in the making would learn from great masters, with no pressure whatsoever to perform or meet deadlines. I know I did. That just was not the case.

“On the ground floor was a store and workroom, open to the street, where the artisans and apprentices mass-produced products. The goal was to produce a constant flow of marketable art and artifacts rather than nurture creative geniuses yearning to find outlets for their originality.”

So no illusions here: this was a for-profit enterprise with ambitious production and commercial goals to be met. And yet, it had a strong learning culture, one that would profoundly influence Leonardo. What was special about this place then? And why does it matter today anyway?

“The fifteenth century of Leonardo and Columbus and Gutenberg was a time of invention, exploration and the spread of knowledge by new technologies. In short, it was a time like our own.”

Now that we got the second question cleared out, let’s dive into the main characteristics of this Renaissance italian workshop:

The learning program was long and eclectic. Leonardo’s apprenticeship took six years to complete (!) and wasn’t limited to drawing techniques; a well-rounded curriculum covered subjects such as mechanics, math, anatomy, music and philosophy.

There was a sense of community. Many of the artists working with Verrocchio actually lived in his studio, upstairs from the store. Leonardo himself, after finishing his apprenticeship at twenty years old, decided to continue living there.

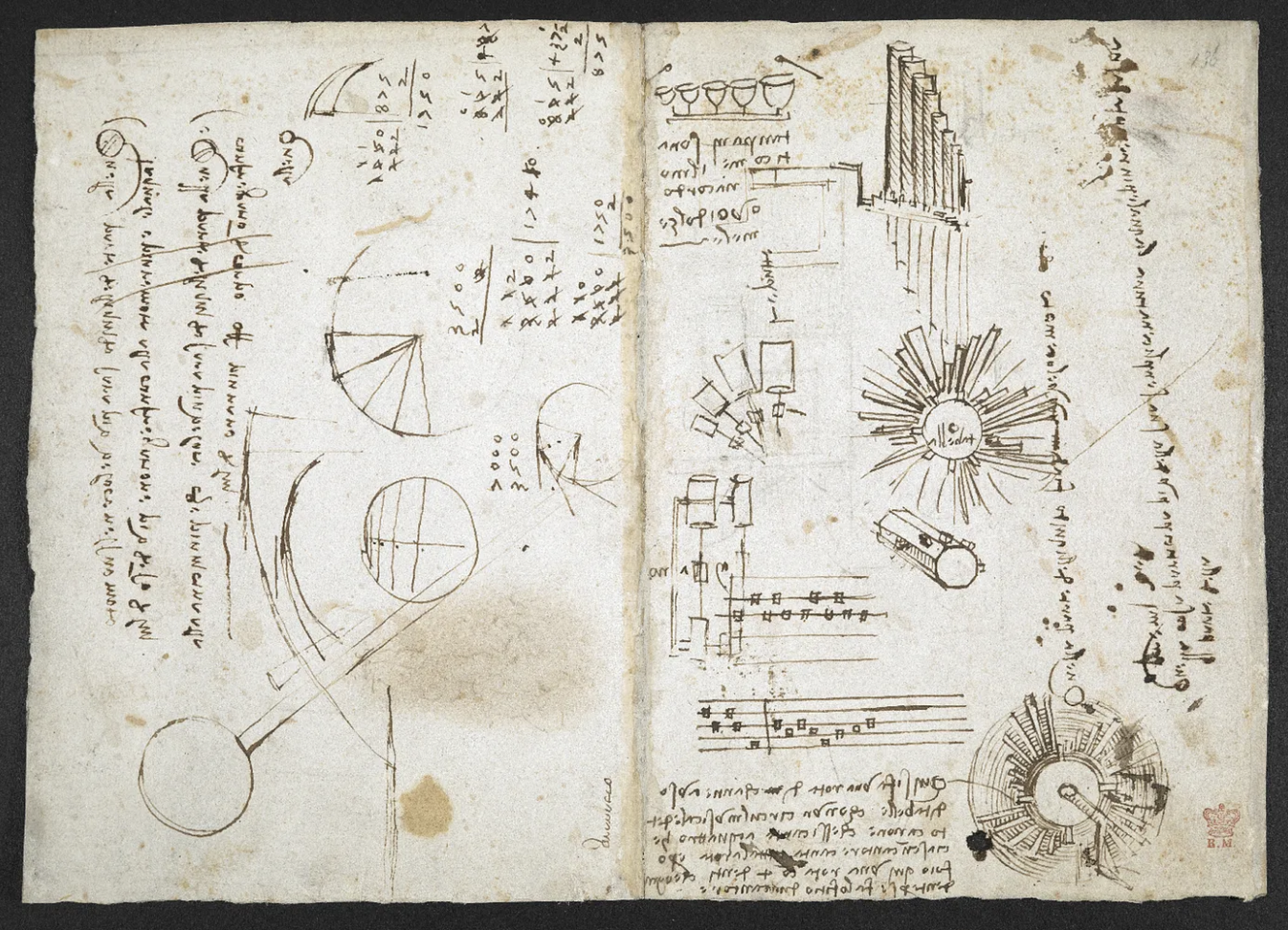

Experiments were encouraged. Artists at Verrocchio’s studio conducted drawing studies to explore the effects of light and shade on draperies. While some of these drawings were the basis for future paintings, others were done just for the sake of learning.

Learning meant more than hierarchy. Leonardo experimented with oil painting, even though his Master Verrocchio never did. Then he took it to the next level, introducing a new technique called sfumato that would turn out to be a trademark of his paintings.

Ego was kept in check. Art pieces were not signed, and they were produced by different artists working in collaboration. That’s why specialists today have a real hard time determining who painted what (even when it comes to Leonardo).

. . .

If the Renaissance days were in fact anything like our own, we might want to stand back a little and ask ourselves:

Are we taking the time to learn and connect the dots?

Are we working to build communities around our interests?

Are we using a trial-and-error approach when it comes to learning?

Are we being brave enough to push through the limits of knowledge?

Are we really, selflessly, collaborating with those around us?

I would love to hear your thoughts.

. . .

All of the above quotes are from Leonardo da Vinci’s biography by Walter Isaacson.